The future (if you want it to be)

Disclaimer

By Michael Kanellos

Staff Writer, CNET News.com

August 23, 2004 4:00 AM PT

There's not a lot of middle

ground on the subject of implanting electronic identification chips in

humans.

There's not a lot of middle

ground on the subject of implanting electronic identification chips in

humans.

Advocates of technologies like radio frequency identification tags say their potentially life-saving benefits far outweigh any Orwellian concerns about privacy. RFID tags sewn into clothing or even embedded under people's skin could curb identity theft, help identify disaster victims and improve medical care, they say.

Critics, however, say such technologies would make it easier for government agencies to track a person's every movement and allow widespread invasion of privacy. Abuse could take countless other forms, including corporations surreptitiously identifying shoppers for relentless sales pitches. Critics also speculate about a day when people's possessions will be tagged--allowing nosy subway riders with the right technology to examine the contents of nearby purses and backpacks.

"Invasion of privacy is going to be impossible to avoid," said Katherine Albrecht, the founder and director of Consumers Against Supermarket Privacy Invasion and Numbering, or CASPIAN, a watchdog group created to monitor the use of data collected in the so-called loyalty programs used increasingly by supermarkets. Albrecht worries about a day when "every physical item is registered to its owner."

The overriding idea behind tagging people with chips--whether through implants or wearable devices such as bracelets--is to improve identification and, consequently, tighten access to restricted information or physical areas.

But on top of civil liberties and other policy issues, such technologies face visceral objections from many people who frown on the idea of being implanted with tags that can track them like migrating tuna. Complaints have led several companies to abandon plans to use RFID technologies in products, much less in human bodies.

The concept of implanting chips for tracking purposes was introduced to the general public more than a decade ago, when pet owners began using them to keep tabs on dogs and cats. The notion of embedding RFID tags in the human body, though, remained largely theoretical until the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, when a technology executive saw firefighters writing their badge numbers on their arms so that they could be identified in case they became disfigured or trapped.

Richard Seelig, vice president of medical applications at security specialist Applied Digital Systems [Digital Angel], inserted a tracking tag in his own arm and told the company's CEO that it worked. A new product, the VeriChip, was born. See saved original VeriChip website

Applied Digital formed

a division named after the chip and says it has sold about 7,000 of the

electronic tags. An estimated 1,000 have been inserted in humans, mostly

outside the United States, with no harmful physical side effects reported from

the subcutaneous implants, the company said.

Applied Digital formed

a division named after the chip and says it has sold about 7,000 of the

electronic tags. An estimated 1,000 have been inserted in humans, mostly

outside the United States, with no harmful physical side effects reported from

the subcutaneous implants, the company said.

"It is used instead of other biometric applications," such as fingerprints, said Angela Fulcher, vice president of marketing at VeriChip, which is based in Palm Beach, Fla. The basic technology comes from Digital Angel, a sister company under the Applied corporate umbrella that has sold thousands of tags for identifying pets and other animals.

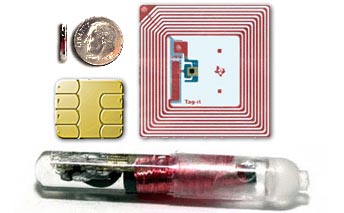

VeriChip makes 11-millimeter RFID tags

that are implanted in the fatty tissue below the right tricep. When near a

scanner, the chip is activated and emits an ID number. When a person's tag

number matches an ID in a database, the person is allowed to enter a secured

room or complete a financial transaction.

VeriChip makes 11-millimeter RFID tags

that are implanted in the fatty tissue below the right tricep. When near a

scanner, the chip is activated and emits an ID number. When a person's tag

number matches an ID in a database, the person is allowed to enter a secured

room or complete a financial transaction.

So far, enhancing physical security--controlling access to buildings or other areas--remains the most common application. RFID chips cannot track someone in real time the way the Global Positioning System does, but they can provide information such as whether a particular individual has gone through a door.

Latin American customers are looking at both technologies for security purposes, which partly explains why some of VeriChip's early clients included Mexico's attorney general, as well as a Mexican agency trying to curb the country's kidnapping epidemic, and commercial distributors in Venezuela and Colombia.

The value of these technologies was underscored recently by a CNET News.com reader who wrote from Puerto Rico to inquire about their development. In her e-mail, Frances Pabon said she hopes that RFID or GPS technologies can be used for her husband, who must travel through neighborhoods in San Juan that are infested with crack dealers.

"I think safeguarding his

safety doesn't necessarily violate his privacy," she wrote. "And if I am made

to choose between keeping him safe versus keeping him private, I'd rather keep

him safe and then change private data such as credit cards, bank accounts,

etc., after."

"I think safeguarding his

safety doesn't necessarily violate his privacy," she wrote. "And if I am made

to choose between keeping him safe versus keeping him private, I'd rather keep

him safe and then change private data such as credit cards, bank accounts,

etc., after."

Safety has been a primary driver in some U.S. applications as well. An Arizona company called Technology Systems International, for example, says it has improved security in prisons with an RFID-like system for inmates and guards. The company's products came out in 2001 and are based on technology licensed from Motorola, which created it for the U.S. military to find gear lost in battle.

TSI's wristbands for inmates transmit signals every two seconds to a battery of antennas mounted in the prison facility. By examining the time the signal is received by each antenna, a computer can determine the exact location of each prisoner at any given time and can reconstruct prisoners' movements later, if necessary to investigate their actions.